From the desk of Daniel Edwins:

When was the last time you were frustrated using something in your daily life?

I was recently staying at a cabin on Lake Superior with my family and was prepping ingredients to make homemade pizzas. But I couldn’t open the canned tomatoes using the cabin’s can opener! As someone who has a formal user experience design education and loves product design, I analyzed the can opener for 15 minutes, tried to identify its signifiers and affordances, and I still wasn’t able to use it! Ultimately, I needed to watch a tutorial to figure it out.

What went wrong?

It was actually a great can opener with features I didn’t even know about. So what went wrong? Maybe I’m dumber than I thought. Or maybe I have a mental model of how a can opener works, and this can opener didn’t fit into that model. As humans, we all have different mental models for things in everyday life based on our perceptions, knowledge and experiences.

Here are some examples of how different mental models can be:

- Perhaps my mental model for can openers is too limited.

- Perhaps this can opener is so different that it doesn’t fit into many people’s mental models.

- Perhaps someone using this can opener has arthritis.

- Perhaps another has never used a can opener.

How do can openers relate to websites or other digital products?

If I design a website without listening to others, I am only designing for people like me who share my mental models and biases. In other words, by designing for myself, I am excluding other people’s perceptions, knowledge and experiences from the process. By excluding others, I am intentionally or unintentionally creating something that’s more difficult for someone else to use. Or in more extreme cases, something can be problematic or harmful for someone else to use.

And that’s why researching and designing for users is important.

Did you notice that I immediately blamed myself when I couldn’t figure out how to use the can opener? As users, it’s too easy to blame ourselves. The can opener company could have designed a more usable product. The Airbnb host could have had instructions on how to use the can opener. Instead of users feeling dumb or blaming themselves, the onus is on us to create better digital products. When we design products with a user experience design process, we’re listening to users, developing empathy for them and creating something better specifically for them.

What is user experience (UX) design, anyway?

Even though design is in the name, only part of UX design is what people usually consider design. It’s less about drawing pixels and vectors on a screen and more about managing the entire creative process to meet users’ needs for your business.

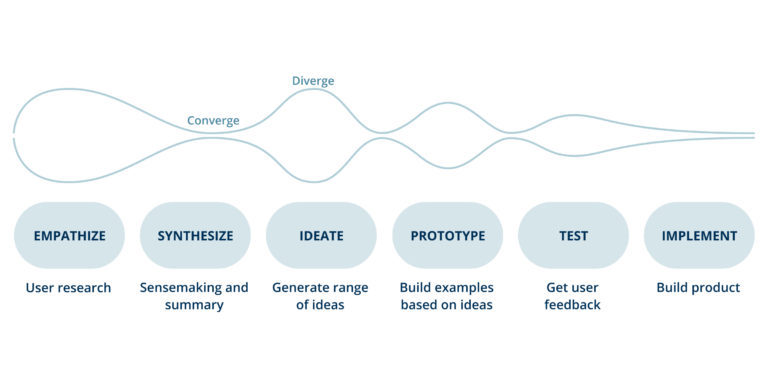

The user experience design process looks something like this:

Overall, this process involves cycles of divergent and convergent thinking: we can expand our thoughts wide – like the divergent thinking that naturally happens in a brainstorm. And then develop consensus and narrow our focus back down. Over and over again. These cycles add some jiggle to the process so that we don’t settle on conventional approaches too quickly. Here is a quick overview of the process:

- Empathize: conduct user research and test any assumptions you’re bringing to the project. In general, we like to collect both qualitative and quantitative data and evaluate what users say they do compared to what they actually do.

- Synthesize: make sense of the research, look for patterns and combine with business strategies and goals.

- Ideate: generate a range of ideas based on our research sensemaking.

- Prototype: build simple examples based on our ideation.

- Test: get user feedback on the prototypes and revise the prototypes to make them better.

- Implement: start building the product based on the research and prototypes.

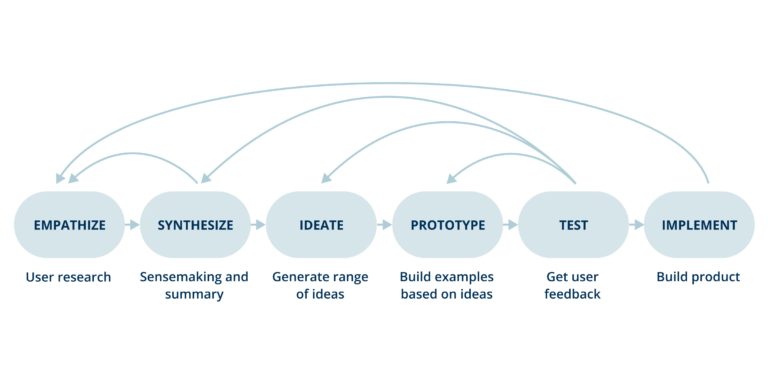

The process outlined above may look linear, but in practice, it’s an iterative process where we build on previous steps and revisit steps to improve the end product. So in the end, the process might look something more like this:

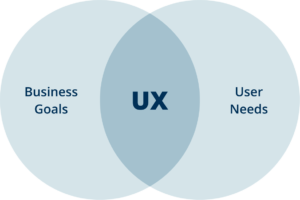

When we work with our clients, we focus on the sweet spot between what your users need and your business goals. This sounds simple enough, but you would be amazed how rare it is to accomplish both the user and business needs – mainly because people don’t think about their users.

When we work with our clients, we focus on the sweet spot between what your users need and your business goals. This sounds simple enough, but you would be amazed how rare it is to accomplish both the user and business needs – mainly because people don’t think about their users.

Can I talk to an average user instead?

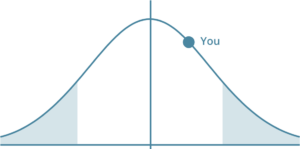

Talking to someone is generally better than talking to no one. But unfortunately, there is no average user – and if we design everything based on average data, we end up with a product that is usable by no one. Instead of thinking in terms of averages, we suggest thinking about the extremes. Remember, you’ll gain more insights by talking to people who have different perceptions, knowledge and experiences (i.e., mental models).

- Consider the person who uses your product all day, every day vs. once in the past year

- Consider the person who has a disability

- Consider the person who has a different background than you

- And remember to consider different user types, cultures, races, religions, ages, education levels, genders, sexual orientations and disabilities

Don’t think your audience is that diverse? Let’s consider disabilities. People can have:

- Permanent disabilities (lost an arm)

- Temporary disabilities (broke an arm)

- Situational disabilities (a new parent holding a baby)

This example was from Microsoft’s wonderful Inclusive 101 Toolkit.

Being inclusive and designing for extreme users has a bigger impact than you can imagine. By designing for someone with one or no arms, it also helps a parent who is working while holding a baby in one arm.

By designing for the extremes, we are making products that are more usable for everyone.

Get started using UX design today

In summary, the UX design process allows us to:

- Test any assumptions about the problem

- Develop empathy for users

- Validate potential solutions with users

And this results in:

- Finding issues and pivoting earlier rather than later

- Satisfying user needs

- Improving your business’ ROI

Anytime you look beyond yourself or your company and start thinking about your users’ needs, this will result in a better end product. Some ways you can get started include:

On your next project, start listing any assumptions you’re making

- Check your assumptions with team members.

- Which voices are you excluding from the decision making process?

- Consider whether talking to your users or stakeholders would be useful.

Start framing problem questions as “How might we?” statements

- This is a great way to practice divergent thinking.

- It also keeps you focused on the problem at hand.

- For example, “How might we create a safer and cleaner can opener?”

Reframe tasks as user stories

- This is an easy way to connect tasks to users and business goals.

- “As a [user type], I want [functionality] so that [benefit].”

- For example, instead of “make handle bigger,” you can say the following: “As a person with arthritis, I want a bigger can opener handle so that I can open cans with less or no pain.”

See? That’s not so difficult.

We’re here to help!

Want to learn more about UX design or incorporate it into your next project? Email Daniel, one of our UX specialists.

Daniel Edwins has been at Neuger for 14 years and completed his Master of Professional Studies in User Experience Design at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in 2021.